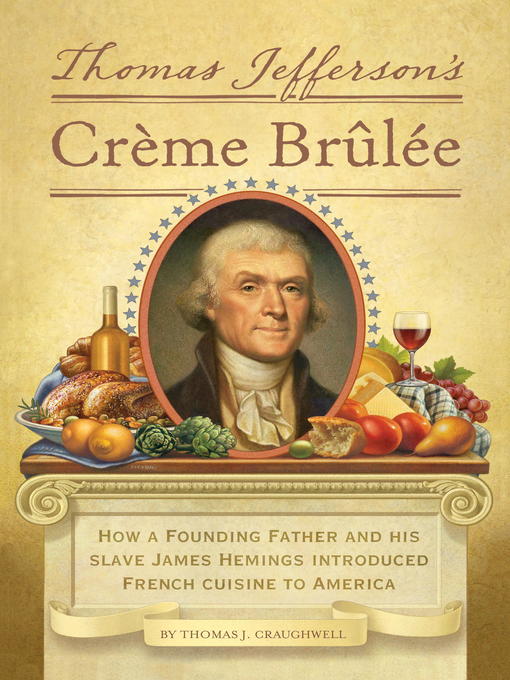

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson struck a deal with his slave, James Hemings. The Founding Father was traveling to Paris and wanted to bring James along “for a particular purpose”— to master the art of French cooking. In exchange for James’s cooperation, Jefferson would grant his freedom.

So began one of the strangest partnerships in United States history. As Hemings apprenticed under master French chefs, Jefferson studied the cultivation of French crops (especially grapes for wine-making) so they might be replicated in American agriculture. The two men returned home with such marvels as pasta, French fries, Champagne, macaroni and cheese, crème brûlée, and a host of other treats. This narrative history tells the story of their remarkable adventure—and even includes a few of their favorite recipes!

-

Creators

-

Publisher

-

Release date

September 18, 2012 -

Formats

-

Kindle Book

-

OverDrive Read

- ISBN: 9781594745799

-

EPUB ebook

- ISBN: 9781594745799

- File size: 6194 KB

-

-

Accessibility

-

Languages

- English

-

Reviews

Loading

Formats

- Kindle Book

- OverDrive Read

- EPUB ebook

Languages

- English

Why is availability limited?

×Availability can change throughout the month based on the library's budget. You can still place a hold on the title, and your hold will be automatically filled as soon as the title is available again.

The Kindle Book format for this title is not supported on:

×Read-along ebook

×The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. Learn more here.